- History of the Republican Party

The Creation

The Republican Party, also known as the GOP (Grand Old Party), is one of the two principal political parties in the United States. It is the second-oldest existing political party in the nation, following its main political rival, the Democratic Party. Prior to achieving this status, the American political landscape was dominated by the Whigs and Democrats for decades leading up to the Civil War. However, by the 1850s, internal divisions within the Whig Party had rendered it a coalition of conflicting interests. An emerging anti-slavery faction clashed with a traditionalist and increasingly pro-slavery Southern faction.

These internal conflicts reached a critical point in the 1852 election, where the Whig candidate, Winfield Scott, was decisively defeated by Franklin Pierce. Southern Whigs, disillusioned by their previous support for Whig President Zachary Taylor, were reluctant to back another Whig candidate. Despite being a slaveowner, Taylor had adopted a notably anti-slavery stance after a neutral campaign, alienating his Southern supporters. The loss of Southern support, coupled with Northern votes shifting to the Free Soil Party, signaled the end for the Whigs. Consequently, the Whig Party never again contested a presidential election.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act, enacted by Democrats in 1854, dealt the decisive blow to the Whig Party. Concurrently, it served as the catalyst for the emergence of the Republican Party, which welcomed dissatisfied Whigs and Free Soilers. This formation marked the establishment of an anti-slavery political entity, a direction the Whigs had long resisted.

In response to the extension of slavery into western territories following the enactment of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, the Republican Party emerged. The initial suggestion of the name “Republican” for a new anti-slavery party took place during the first anti-Nebraska local meeting held in a Ripon, Wisconsin schoolhouse on March 20, 1854. Subsequently, the first statewide convention under the Republican banner was convened near Jackson, Michigan, on July 6, 1854. During this assembly, the party articulated its opposition to the expansion of slavery into new territories and nominated a slate of candidates for statewide offices.

The inaugural Republican convention took place on September 20, 1854, at the First Congregational Church in Aurora, Illinois, where a “People’s Convention” convened to deliberate on the issue of slavery. L.D. Brady assumed the role of chairman for this historic gathering, which saw the participation of 208 delegates chosen specifically to establish an anti-slavery political entity. It was during this convention that the name “Republican” was officially adopted, alongside the formulation of a platform that would later underpin the famed Lincoln-Douglas debates.

In its early stages, the Republican Party comprised northern Protestants, factory workers, professionals, businessmen, affluent farmers, and, following the Civil War, emancipated African American individuals. During this period, the party garnered minimal support from white Southerners, who predominantly aligned with the Democratic Party in the Solid South, as well as from Irish and German Catholics, constituting significant Democratic voting blocs. Assertively opposing slavery expansion before 1861, the party spearheaded efforts to dismantle the Confederate States of America during the period spanning 1861 to 1865.

While the Republican Party initially held negligible influence in the Southern United States, it experienced considerable success in the Northern region. By 1858, the party had effectively mobilized former Whigs and Free Soil Democrats to establish majorities in nearly every Northern state.

Amidst the heightened tensions between the North and South during the 1860 presidential campaign, Abraham Lincoln delivered his renowned Cooper Union speech, addressing the severe persecution faced by Republicans in the Southern states:

When you speak of us Republicans, you do so only to denounce us as reptiles, or, at the best, as no better than outlaws. You will grant a hearing to pirates or murderers, but nothing like it to “Black Republicans.” … But you will not abide the election of a Republican president! In that supposed event, you say, you will destroy the Union; and then, you say, the great crime of having destroyed it will be upon us! That is cool. A highwayman holds a pistol to my ear, and mutters through his teeth, “Stand and deliver, or I shall kill you, and then you will be a murderer!”

The Election of Abraham Lincoln

Following the election of its inaugural president, Abraham Lincoln, in 1860, and the Republican Party’s pivotal role in securing the Union’s triumph in the Civil War, as well as its instrumental contribution to the abolition of slavery, the party exerted significant influence over the national political landscape until 1932. Lincoln’s ascension to the presidency in 1860 heralded a new epoch of Republican dominance, anchored in the industrial North and agricultural Midwest. Skillfully unifying disparate factions within his party, Lincoln adeptly marshaled support for the Union cause during the Civil War, albeit facing opposition from Radical Republicans advocating for more stringent measures.

Amidst this political backdrop, numerous conservative Democrats aligned with the War Democrats, driven by a staunch belief in American nationalism and a commitment to supporting the war effort. Lincoln’s inclusion of the abolition of slavery as a war objective galvanized the Peace Democrats, who made significant gains in various state races, particularly in Connecticut, Indiana, and Illinois. While the majority of state Republican parties embraced the antislavery agenda, Kentucky stood as an exception.

The Republicans condemned the peace-oriented Democrats, labeling them as disloyal Copperheads, and successfully garnered enough support from War Democrats to maintain their majority in 1862. In 1864, they forged a coalition with numerous War Democrats under the banner of the National Union Party. President Lincoln, in a strategic move, selected Democrat Andrew Johnson as his running mate, securing his re-election with ease.

Throughout the conflict, affluent men in major urban centers established Union Leagues to advocate for and financially support the war effort. Following the 1864 elections, Radical Republicans, led by figures such as Charles Sumner in the Senate and Thaddeus Stevens in the House, assumed a prominent role, advocating for more assertive measures against slavery and a harsher stance towards the Confederates.

Under the leadership of the Republican-controlled Congress, the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which prohibited slavery nationwide, secured passage in the Senate in 1864 and the House in 1865, ultimately receiving ratification in December 1865. The surrender of the Confederacy in 1865 marked the conclusion of the Civil War. Tragically, President Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865, leading to the ascension of Andrew Johnson to the presidency.

Post-civil War Reconstruction 1865–1877

Following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and throughout the post-Civil War Reconstruction period, significant discord arose regarding the treatment of ex-Confederates and freedmen, formerly enslaved individuals. Both white Republicans and Democrats sought the support of black voters, albeit with reluctance to grant them political nominations, often reserving such positions for whites unless deemed necessary. Consequently, these half-hearted gestures failed to satisfy either black or white Republicans, underscoring the inherent shortcomings within the party.

A critical flaw plaguing the Republican Party in Alabama, and indeed across the South, was its inability to establish a biracial political coalition. Despite fleeting moments of power, the party proved ineffective in shielding its members from the rampant Democratic violence and intimidation tactics. As a result, Alabama Republicans found themselves in a perpetual state of defensiveness, both verbally and physically.

Over time, societal pressures compelled the majority of Scalawags to align with the conservative Democratic Redeemer coalition. However, a minority persisted and, from the 1870s onward, constituted the “tan” segment of the “Black and Tan” Republican Party, a minority presence across all Southern states after 1877. This division within the party resulted in two distinct factions: the predominantly white “lily-white” faction and the biracial “black-and-tan” faction.

In several Southern states, the “Lily Whites,” aiming to attract white Democrats to the Republican Party, endeavored to purge or diminish the influence of the Black and Tan faction. Notable among these “Lily White” leaders in the early 20th century was Arkansas’ Wallace Townsend, who served as the party’s gubernatorial nominee in 1916 and 1920, as well as its veteran national GOP committeeman. Factional tensions surfaced prominently in 1928 and again in 1952, culminating in the ultimate triumph of the lily-white faction in 1964.

Gradual Move Away of African-American from Republican Party

In the late 1870s, the Republican Party underwent internal divisions, leading to factionalism. The Stalwarts, adherents of Senator Roscoe Conkling, staunchly defended the spoils system, while the Half-Breeds, led by Senator James G. Blaine of Maine, advocated for civil service reform. A faction of upscale reformers, known as “Mugwumps,” vehemently opposed the spoils system altogether.

In the 1884 presidential election, Mugwumps rejected James G. Blaine due to allegations of corruption and threw their support behind Democrat Grover Cleveland, though the majority eventually returned to the Republican Party by 1888. Prior to the 1884 Republican National Convention, Mugwumps strategically mobilized in key swing states, notably New York and Massachusetts. Despite their efforts to block Blaine’s nomination, many Mugwumps defected to the Democrats, who had put forward reformer Grover Cleveland as their candidate. Notably, young leaders such as Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge, committed to reform, chose to remain within the Republican Party, a decision that solidified their leadership positions within the GOP.

As early as 1876, well before the suggested year of 1960 put forth by the Philadelphia conventioneers, Republican leaders commenced a departure from their support of black Americans. During the presidential election of that year, Ohio Republican Rutherford B. Hayes made a concession by agreeing to remove federal troops from the South in exchange for Southern Democratic backing. This agreement enabled Democrats to ascend to power in the South, ultimately instituting legalized segregation.

The election of William McKinley in 1896 signaled a resurgence of Republican dominance and constituted a realigning election. With a distinct advantage nationwide and in the industrial states, the GOP eclipsed the Democrats, who retained control primarily in the Solid South with limited opportunities elsewhere. Major cities were either under Republican or Democratic machines, leading to a decline in voter turnout due to fewer competitive states.

In this era, remaining black voters in the South lost their voting rights in general elections but still retained a voice in the Republican National Convention. Meanwhile, a wave of new immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe arrived, with the Jewish community showing a preference for socialism, while others were largely disregarded by political machines as their votes were deemed unnecessary.

Simultaneously, the women’s suffrage movement gained momentum, particularly in Western states, where it achieved increasing success.

In 1912, Theodore Roosevelt, a former Republican president, established the Progressive Party after facing rejection from the GOP. He subsequently ran as a third-party presidential candidate advocating for social reforms, albeit unsuccessfully. Following the 1912 election, numerous supporters of Roosevelt departed from the Republican Party, precipitating an ideological shift to the right within the party.

Amidst the Great Depression spanning from 1929 to 1940, the GOP experienced a loss of its congressional majorities. Concurrently, under the leadership of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Democrats forged a formidable New Deal coalition, which maintained dominance from 1932 through 1964.

Despite the passage of an anti-lynching bill by House Republicans in January 1922, their counterparts in the Senate refused to enact it. Notably, Heartland Republicans like William Borah of Idaho joined forces with Southern Democrats to thwart the bill’s passage, citing concerns over federal encroachment on states’ autonomy.

Conversely, Democrats began to secure the allegiance of black Americans, a loyalty that persists to this day. As African-Americans migrated from the South to northern cities, Democratic political machines actively integrated these newcomers. In contrast, Republican machines exhibited a tepid response when approached by black leaders seeking to join their ranks.

The transition of black Americans to the Democratic Party solidified during the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt. Despite winning just 23 percent of the black vote in 1932, FDR significantly increased his support among this demographic through his relief policies. The Great Depression disproportionately impacted black Americans, and initiatives like the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Public Works Administration provided crucial assistance to them.

By the 1950s, the symbolic association of the Republicans as the “party of Lincoln” had largely lost its significance. The era of racial liberalism within the GOP culminated with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, marking its final notable moment.

Following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the implementation of the Southern strategy, the Republican Party witnessed a transformation in its core base. Southern states increasingly leaned towards the Republican Party in presidential elections, while Northeastern states became more reliably Democratic. White voters, particularly, began to identify more closely with the Republican Party starting from the 1960s.

In the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Roe v. Wade in 1973, the Republican Party took a firm stance against abortion in its party platform, subsequently bolstering its support among evangelical voters. The party achieved significant electoral success, winning five out of the six presidential elections from 1968 to 1988.

During the tenure of two-term President Ronald Reagan, serving from 1981 to 1989, the Republican Party experienced a transformative period. Reagan’s conservative agenda advocated for reduced social government spending and regulation, increased military expenditure, lower taxes, and a staunch anti-Soviet Union foreign policy. His influence continued to shape the party’s trajectory well into the next century.

In 2016, businessman and former reality TV personality Donald Trump secured the Republican Party’s nomination for president, subsequently winning the presidency and further shifting the party towards the right. Presently, the Republican Party espouses principles of free market economics, cultural conservatism, and originalism in constitutional jurisprudence. Notably, the party boasts the distinction of having produced 19 presidents, the highest tally from any single political party.

- The Black Roots in Politics: The Relationship of African Americans and the Republican Party

The Republican Party, often referred to as the “Grand Old Party,” has undergone a significant evolution in its interactions with the African American community. Over time, a series of historical decisions and the ongoing evolution of the Republican platform have led many within the black community to conclude that the actions of the “Party of Lincoln,” which once championed their emancipation from slavery, no longer align with their interests. Despite this, the Republican Party remains hopeful of revitalizing its relationship with the African American community.

In the latter half of the 1980s, prominent Republican figure Lee Atwater emphasized that in order for the “Grand Old Party” to secure majority support, it must garner the backing of at least 20% of the African American electorate. As the proportion of white Americans in the overall US population continues to decrease, the Republican Party cannot afford to disregard the significant electoral influence wielded by African Americans, who represent over 12% of the country’s population.

Throughout its existence, the Republican Party has experienced significant shifts in its relationship with the African American community. Established in 1854, the Republicans emerged as staunch opponents of the institution of slavery in the United States from their inception. During the American Civil War (1861–1865), Republican President Abraham Lincoln prioritized the abolition of slavery as a key objective for the Northern states in their conflict against the seceding Confederate states, predominantly led by Southern Democrats. The enactment of the Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution on December 18, 1865, which outlawed slavery nationwide, galvanized the black population in support of the Republican Party as their liberators.

During the Reconstruction era (1865–1877), African Americans emerged as a bastion of support for the Republican Party in the former Confederate states. The enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) and Fifteenth Amendment (1870) to the Constitution, granting civil and political rights to freedmen, facilitated significant transformations in the political, economic, and socio-cultural landscape of the US South. Eager to leverage politics as a means of upward mobility, African Americans actively aligned themselves with the “Party of Lincoln.”

For the first time in history, African Americans secured representation in the US federal Congress, with 22 black Republican representatives serving throughout the entire Reconstruction era. While black sheriffs, tax collectors, and other officials emerged in counties and cities with significant African American populations in the Southern states, white administrators still occupied 80% of elected positions. It is noteworthy that despite these advancements, the socio-economic conditions for the majority of the African American community in the South remained exceedingly challenging—the long-awaited promise of “40 acres and a mule” under the Republican-led federal government remained unfulfilled.

Recognizing that the South no longer posed a threat to national unity, Republican Party leadership in the 1870s sought to redirect the focus of its electoral base from African Americans to affluent and middle-class white Southerners, many of whom had previously been disenfranchised for their involvement in the rebellion. Consequently, the conclusion of the Reconstruction era witnessed a resurgence of Democratic Party power in the region, with concerted efforts to curtail the voting rights of the black population through the implementation of property and educational requirements, alongside the widespread establishment of racial segregation policies aimed at solidifying the secondary status of African Americans in the Southern states.

In a bid to reclaim their former influence in the South, Republicans repeatedly introduced bills in the US Congress aimed at promoting African American education through public funding and access to private resources, as well as advocating for federal oversight of voter registration and elections. The failure of these measures, which had the potential to disrupt the political framework established by Southern Democrats, ultimately led to the resignation of Republicans to Democratic Party dominance in the South.

While unable to substantially alter the status of African Americans in the US South, the Republican Party nonetheless maintained a semblance of advocating for the interests of the black population. Republican presidents continued to exhibit paternalistic attitudes towards African Americans, albeit to a lesser extent than during the Reconstruction era. Given the Democratic Party’s less favorable stance towards African Americans, the black population predominantly aligned with the Republicans, viewing them as a bulwark against the proliferation of legislative racism beyond the Southern states.

However, during the 1928 presidential campaign, Republican Party candidate Herbert Hoover adopted a new “Southern strategy” to court the votes of the local white population. In addition to pledging to modernize the agrarian region, Hoover voiced support for policies of racial segregation, a stance that significantly eroded support for the “Party of Lincoln” within the African American community.

The repercussions of the “Great Depression” of 1929–1933, compounded by the subsequent “New Deal” under Democratic President Franklin Roosevelt, which aimed at extensive socio-economic transformations, marked the onset of significant shifts in the electoral preferences of the African American community. While the Democrats made no attempts to alter the prevailing racial hierarchy in the South, they actively pursued paternalistic policies towards African Americans in the major cities of the Northeast and Midwest. In a notable development, black delegates were even granted admission to the party’s national convention in 1936.

It is noteworthy that despite the Democrats’ inaction on racial segregation in the South, their nomination of Roosevelt garnered substantial support among African Americans. Roosevelt secured over 70% of the black vote in the elections, surpassing the party’s overall rating among black voters.

In the 1960 elections, Democratic candidate John F. Kennedy successfully rebranded his party, positioning it as a progressive political entity. Throughout his campaign, Kennedy’s meeting with African-American civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. resonated deeply with the black population. Despite Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, which tragically occurred before a legislative resolution to the civil rights issue, federal authorities remained steadfast in their commitment to advancing civil rights reforms.

In 1964, the US Congress, with bipartisan backing, enacted the Civil Rights Act, a landmark piece of legislation that prohibited racial discrimination in trade, services, and employment.

The Republican Party’s conservative shift persisted under Richard Nixon. Despite establishing the Office of Minority Affairs in 1969 and the National Council of Black Republicans, Republicans increasingly aligned themselves as a predominantly white majority party. With the “Party of Lincoln” solidifying its support among white voters in the South, the loss of African American votes appeared as an acceptable casualty.

Conversely, Democrats courted black voters by expanding the welfare system, embracing political paternalism towards racial and ethnic minorities, and bolstering federal intervention in socio-economic matters. In the late 1970s, Republicans sought to educate middle and upper-class African Americans on the advantages of free-market socioeconomic policies through a prominent network of African-American conservative scholars and experts.

However, the policies pursued by the Republican administration of Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, including tax reductions, social security cuts, diminished federal intervention in states’ affairs, and stricter criminal justice measures, were perceived by African Americans as detrimental to their community’s interests.

The African-American community viewed the emergence of a new wave of black political conservatism not as an organic ideology that arose from grassroots movements, but rather as a model imposed from the top down, reflecting desired interracial relations in the eyes of white Americans. A considerable portion of the black population came to believe that the policies of the Republican Party, despite any individual benefits within its programs, were primarily perceived as racist and discriminatory against the African American community.

- Key Figures of The Republican Party

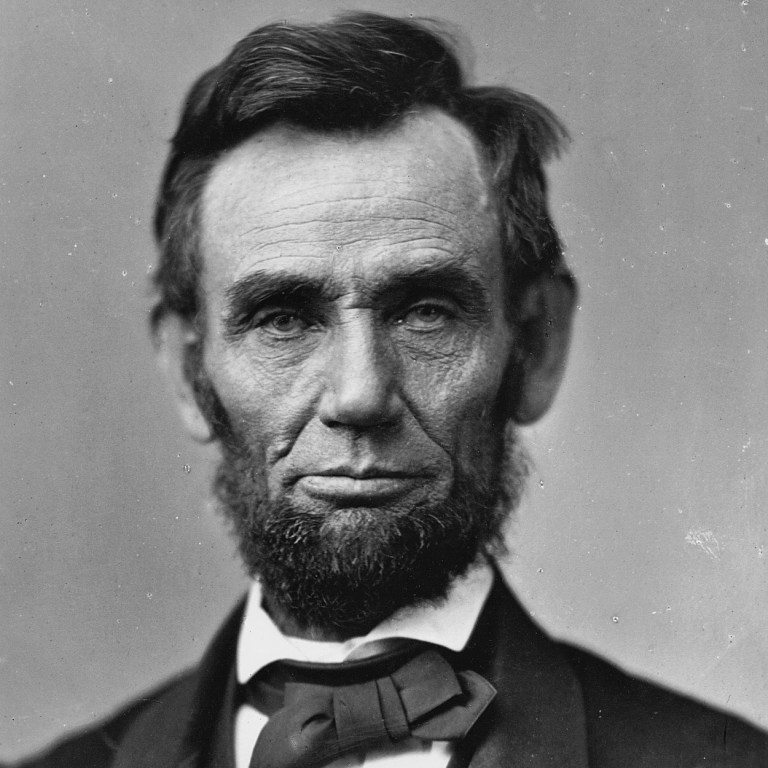

- Abraham Lincoln:

Background

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, in a log cabin in Hardin County (now LaRue County), Kentucky. His early life was marked by hardship and limited formal education. Despite these challenges, Lincoln developed a passion for reading and self-education, which laid the foundation for his future career. He moved with his family to Indiana in 1816 and then to Illinois in 1830, where he eventually settled in the town of New Salem.

Lincoln’s political career began in the Illinois State Legislature, where he served from 1834 to 1842. He was a member of the Whig Party, and during this time, he became known for his opposition to the spread of slavery. In 1846, Lincoln was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, serving a single term. His opposition to the Mexican-American War and his moderate stance on slavery made him a controversial figure.

Lincoln’s return to politics in the 1850s was spurred by the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, which allowed new territories to decide on the legality of slavery through popular sovereignty. Outraged by this threat to the Missouri Compromise and the potential spread of slavery, Lincoln joined the newly formed Republican Party, which was dedicated to preventing the expansion of slavery into the western territories.

Contribution to Anti-Slavery

Lincoln’s contributions to the anti-slavery cause through the Republican Party were profound and far-reaching. His political strategy, public speeches, and ultimately his presidential actions were instrumental in shaping the course of American history.

- 1858 Senate Campaign: Lincoln gained national prominence during his 1858 campaign for the U.S. Senate against Stephen A. Douglas. Although he lost the election, the debates between Lincoln and Douglas highlighted the moral and political divisions over slavery. Lincoln’s famous “House Divided” speech, delivered in Springfield, Illinois, on June 16, 1858, articulated his belief that the nation could not endure permanently half slave and half free.

- 1860 Presidential Election: Lincoln was elected as the 16th President of the United States on November 6, 1860, as the candidate of the Republican Party. His election was a turning point in the anti-slavery movement. The southern states viewed his victory as a direct threat to the institution of slavery, leading to the secession of several states and the formation of the Confederate States of America.

- Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation: The Civil War began in April 1861, shortly after Lincoln took office. Initially, Lincoln’s primary goal was to preserve the Union, but as the war progressed, he recognized that ending slavery was essential to winning the war and ensuring the nation’s future. On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that all slaves in Confederate-held territory were to be set free. Although it did not immediately free all slaves, it was a crucial step towards abolition and allowed for the enlistment of African American soldiers in the Union Army.

- Gettysburg Address: Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, delivered on November 19, 1863, at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, reinforced the moral imperative of the war. In his brief but powerful speech, Lincoln emphasized the principles of human equality and the fight for a new birth of freedom, ensuring that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

- 13th Amendment: Lincoln’s most significant legislative achievement was his support for the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which sought to abolish slavery entirely in the United States. Lincoln worked tirelessly to ensure its passage, seeing it as a necessary legal conclusion to the Emancipation Proclamation. The amendment was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, and by the House of Representatives on January 31, 1865. It was ratified by the states and officially adopted on December 6, 1865, after Lincoln’s assassination.

- Thaddeus Stevens:

Background

Thaddeus Stevens was born on April 4, 1792, in Danville, Vermont. Born into a poor family, Stevens faced numerous hardships early in life, including being born with a clubfoot, which made him a target for ridicule and bullying. Despite these challenges, he demonstrated remarkable academic talent. Stevens attended Dartmouth College, graduating in 1814. After college, he moved to Pennsylvania, where he studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1816.

Stevens settled in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, where he established a successful legal practice. He quickly became known for his sharp intellect, formidable oratory skills, and unyielding principles. These qualities propelled him into politics, where he initially aligned with the Anti-Masonic Party and later the Whig Party. Stevens was a staunch advocate for public education, helping to establish Pennsylvania’s public school system.

Stevens’s early political career was characterized by his strong opposition to slavery. He became increasingly involved in the abolitionist movement, using his legal and political skills to fight against the institution of slavery and for the rights of African Americans.

Contribution to Anti-Slavery

Thaddeus Stevens’s contributions to the anti-slavery movement were profound and influential. His work as a congressman, his leadership within the Republican Party, and his unwavering commitment to equality played a crucial role in the fight against slavery and the shaping of post-war America.

- Early Political Career and Abolitionism: Stevens’s anti-slavery stance was evident early in his political career. As a member of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, he opposed the state’s policies that discriminated against African Americans. He fought against legislation that restricted the rights of free blacks and worked to ensure that public education was accessible to all children, regardless of race.

- Formation of the Republican Party: Stevens was a key figure in the formation of the Republican Party in the 1850s. The party was established in response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which allowed for the potential expansion of slavery into new territories. Stevens, along with other anti-slavery Whigs, Free Soilers, and abolitionists, formed the Republican Party with a platform dedicated to stopping the spread of slavery.

- Congressional Leadership: Elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1849, Stevens became a leading voice in Congress against slavery. His fiery speeches and uncompromising stance earned him the nickname “The Great Commoner.” He was a vocal opponent of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and the Dred Scott decision of 1857, which declared that African Americans could not be citizens and that Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery in the territories.

- Civil War and Emancipation: During the Civil War, Stevens was a powerful advocate for the Union cause and for the emancipation of slaves. He played a critical role in shaping wartime policies, including the Confiscation Acts, which aimed to seize property used to support the Confederate war effort, including slaves. Stevens was instrumental in pushing for the Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, which declared all slaves in Confederate-held territory to be free.

- Radical Reconstruction: After the Civil War, Stevens emerged as a leader of the Radical Republicans, a faction within the Republican Party that sought to ensure that the rights of freed slaves were protected and that the South was fundamentally transformed. He played a central role in drafting and advocating for the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, which placed the southern states under military rule and required them to adopt new constitutions guaranteeing black suffrage as a condition for readmission to the Union.

- 14th Amendment: Stevens was a principal architect of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1868. This amendment granted citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, including former slaves, and provided for equal protection under the law. Stevens’s advocacy was crucial in ensuring that the amendment addressed civil rights and citizenship for African Americans.

- Economic and Land Reforms: Stevens also pushed for economic reforms to support freed slaves. He advocated for land redistribution, proposing that large plantations be confiscated and divided among former slaves to provide them with economic independence. Although his land reform proposals were not fully realized, his efforts underscored the importance of economic justice in the fight for civil rights.

- Impeachment of Andrew Johnson: Stevens played a leading role in the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson in 1868. Johnson’s lenient Reconstruction policies and opposition to civil rights for freedmen clashed with the Radical Republicans’ agenda. Stevens led the effort in the House to impeach Johnson, although the Senate ultimately acquitted him by a single vote.

- Salmon P. Chase:

Background

Salmon Portland Chase was born on January 13, 1808, in Cornish, New Hampshire. Raised in a large family, Chase faced early adversity, losing his father at the age of nine. His mother moved the family to Ohio, where Chase attended local schools before enrolling at Cincinnati College and later transferring to Dartmouth College, from which he graduated in 1826.

After studying law under the renowned attorney William Wirt in Washington, D.C., Chase was admitted to the bar in 1829 and began practicing law in Cincinnati, Ohio. During this period, Chase’s exposure to the legal system and his encounters with abolitionists deeply influenced his views on slavery. He quickly established himself as a prominent lawyer and became involved in various anti-slavery causes.

Chase’s legal career was marked by his defense of runaway slaves and his challenge of the constitutionality of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. His work earned him the moniker “Attorney General for Fugitive Slaves” and laid the groundwork for his political career as a staunch abolitionist.

Contribution to Anti-Slavery

Salmon P. Chase’s contributions to the anti-slavery movement were multifaceted and influential. His work as a lawyer, politician, and government official played a crucial role in the fight against slavery through the Republican Party.

- Early Legal Career and Abolitionism: During the 1830s and 1840s, Chase became involved in numerous high-profile cases defending runaway slaves. One notable case was his defense of John Van Zandt in 1842, who was prosecuted for aiding fugitive slaves. Although the case was lost, Chase’s arguments against the Fugitive Slave Act highlighted his commitment to anti-slavery principles.

- Political Rise and the Liberty Party: Chase entered politics with a strong abolitionist stance. In the late 1840s, he was instrumental in forming the Liberty Party, which opposed the expansion of slavery. He played a key role in the party’s platform and was influential in merging it with other anti-slavery factions to form the Free Soil Party in 1848, advocating for “free soil, free labor, and free men.”

- Senator from Ohio: Chase’s political influence grew when he was elected to the U.S. Senate as a Free Soil candidate from Ohio in 1849. During his tenure, he was an outspoken critic of the Compromise of 1850, particularly the Fugitive Slave Act, which required citizens to assist in the capture of runaway slaves. Chase’s speeches and legislative efforts were critical in galvanizing northern opposition to the pro-slavery policies of the federal government.

- Governor of Ohio: Chase served as Governor of Ohio from 1856 to 1860, during which he continued to champion anti-slavery causes. He implemented progressive policies that promoted education and infrastructure, positioning Ohio as a leading state in the fight against slavery. His governorship helped strengthen the Republican Party’s anti-slavery platform and increased his national prominence.

- Role in the Republican Party: As a founding member of the Republican Party, Chase was instrumental in shaping its anti-slavery agenda. He was a key figure at the party’s first national convention in 1856, where he played a significant role in articulating its opposition to the expansion of slavery. His influence helped secure the party’s identity as the primary political force against slavery in the United States.

- Secretary of the Treasury: Appointed by President Abraham Lincoln as Secretary of the Treasury in 1861, Chase’s tenure was marked by significant financial and administrative achievements that supported the Union war effort. He established a national banking system and introduced the issuance of paper currency (“greenbacks”), which were crucial in financing the Civil War. Chase’s financial policies ensured the Union could sustain its military efforts, indirectly contributing to the fight against slavery by supporting the war that ultimately led to emancipation.

- Chief Justice of the Supreme Court: In 1864, Lincoln appointed Chase as Chief Justice of the United States. In this role, Chase continued to influence the nation’s approach to slavery and civil rights. He presided over significant cases, including Texas v. White (1869), which affirmed the permanence of the Union and supported federal authority during Reconstruction. His decisions often reflected his long-standing commitment to civil rights and the principles of the anti-slavery movement.

- William H. Seward:

Background

William Henry Seward was born on May 16, 1801, in Florida, New York. Raised in a well-to-do family, Seward attended Union College, where he graduated in 1820. He studied law under John Duer and Ogden Hoffman in New York City and was admitted to the bar in 1822. Seward moved to Auburn, New York, where he began practicing law and became involved in local politics.

Seward’s early political career was rooted in the anti-Masonic movement, which evolved into his affiliation with the Whig Party. In 1830, he was elected to the New York State Senate, where he championed progressive causes, including public education and prison reform. Seward’s strong stance against slavery emerged during this period, laying the groundwork for his future contributions to the abolitionist movement.

Seward’s marriage to Frances Adeline Miller in 1824 was also significant, as she shared his abolitionist sentiments and influenced his political views. Their home in Auburn became a station on the Underground Railroad, providing refuge for escaped slaves.

Contribution to Anti-Slavery

William H. Seward’s contributions to the anti-slavery cause were significant and multifaceted. His work as a governor, senator, and Secretary of State played a crucial role in shaping the Republican Party’s anti-slavery agenda and advancing the cause of abolition.

- Governor of New York: Seward served as Governor of New York from 1839 to 1843. During his tenure, he promoted progressive reforms, including expanding public education and improving infrastructure. Notably, Seward enacted measures to protect fugitive slaves and oppose the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. His efforts included granting legal protections to runaway slaves and providing state resources to assist them, showcasing his commitment to anti-slavery principles.

- U.S. Senator: Elected to the U.S. Senate in 1849, Seward became a leading voice against the expansion of slavery. He vehemently opposed the Compromise of 1850, particularly the Fugitive Slave Act, which required citizens to assist in the capture of escaped slaves. In a famous speech on March 11, 1850, Seward declared that there was a “higher law than the Constitution” that mandated opposition to slavery, emphasizing moral and ethical imperatives over legalistic arguments.

- Role in the Republican Party: Seward was instrumental in the formation of the Republican Party in the 1850s. As a prominent Whig, he transitioned to the newly formed Republican Party, which was dedicated to preventing the spread of slavery into new territories. Seward’s leadership helped shape the party’s platform, and he was considered a leading contender for the presidential nomination in 1860. Although Abraham Lincoln ultimately secured the nomination, Seward’s influence remained significant within the party.

- Secretary of State: Appointed as Secretary of State by President Abraham Lincoln in 1861, Seward played a crucial role in the Union’s efforts during the Civil War. While his primary responsibilities were in foreign affairs, he also supported Lincoln’s anti-slavery policies and contributed to the diplomatic efforts that kept European powers from recognizing the Confederacy. Seward’s diplomatic skill ensured that foreign intervention did not undermine the Union’s war effort, which was essential for the eventual abolition of slavery.

- Emancipation Proclamation: Seward was a key advisor to Lincoln and supported the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation. On September 22, 1862, following the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam, Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, with Seward’s full backing. The final proclamation, effective January 1, 1863, declared all slaves in Confederate-held territory to be free. Seward’s influence and counsel were vital in shaping this landmark decision, which redefined the Union’s war aims and bolstered the moral cause against slavery.

- Post-War Contributions: After the Civil War, Seward continued to serve as Secretary of State under President Andrew Johnson. He supported the Reconstruction policies that aimed to rebuild the South and integrate formerly enslaved African Americans into American society. Seward also played a role in securing the passage of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery throughout the United States.

- Contributions of African American Republicans:

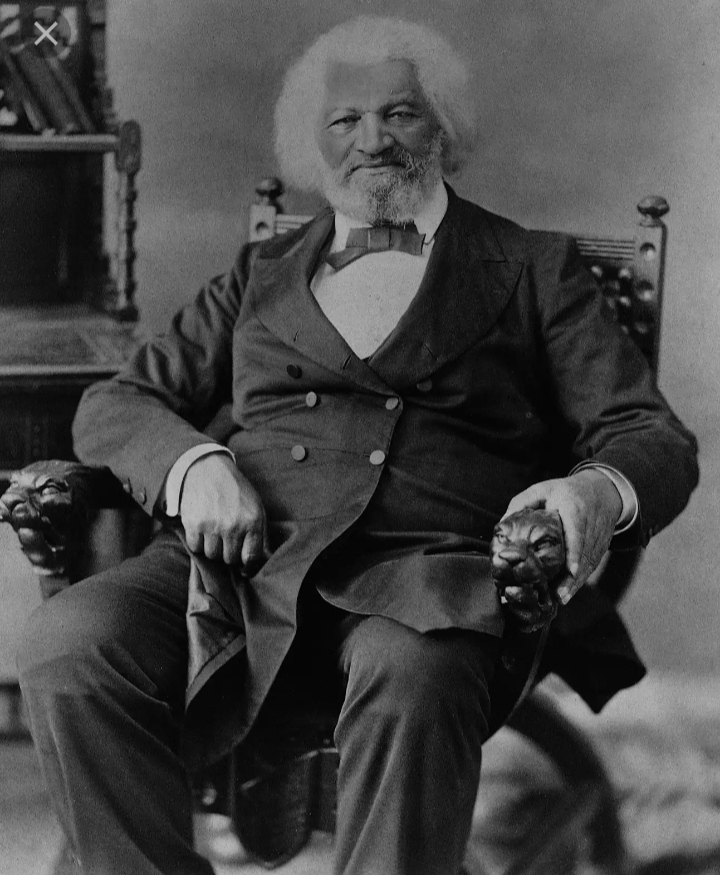

- Frederick Douglass:

Background

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery as Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey on February 14, 1818, in Talbot County, Maryland. His exact date of birth is unknown, and he chose to celebrate it on Valentine’s Day. Douglass was separated from his mother as an infant and raised by his grandmother until the age of seven, when he was sent to the Wye House plantation. As a young boy, he experienced the brutal realities of slavery firsthand.

At the age of 12, Douglass was sent to Baltimore to live with Hugh Auld and his wife, Sophia. Sophia began teaching him the alphabet, but Hugh quickly forbade the lessons, believing that literacy would make Douglass unfit for slavery. Despite this, Douglass continued to learn to read and write in secret, recognizing that education was a pathway to freedom.

In 1838, Douglass escaped from slavery, adopting the name Frederick Douglass to avoid recapture. He settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he began attending abolitionist meetings. His powerful oratory skills and compelling personal narrative quickly garnered attention, and he became a prominent speaker for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society.

Contribution to Anti-Slavery

Frederick Douglass’s contributions to the anti-slavery movement were profound and multifaceted. His work as an orator, writer, publisher, and political activist played a crucial role in advancing the cause of abolition and influencing the Republican Party’s stance on slavery.

- Abolitionist Orator and Writer: Douglass’s eloquence and firsthand accounts of slavery made him one of the most powerful voices in the abolitionist movement. His speeches, such as the famous address “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” delivered on July 5, 1852, in Rochester, New York, highlighted the hypocrisy of a nation that celebrated freedom while perpetuating slavery. In 1845, Douglass published his first autobiography, “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave,” which became a bestseller and exposed the brutal realities of slavery to a broad audience.

- The North Star: In 1847, Douglass founded his own abolitionist newspaper, The North Star, in Rochester, New York. The paper provided a platform for anti-slavery advocacy and addressed issues of racial discrimination and social justice. Through The North Star, Douglass reached a wide audience, influencing public opinion and rallying support for the abolitionist cause.

- Political Involvement and the Republican Party: Douglass became increasingly involved in politics, believing that legal and political action was essential to ending slavery. He supported the formation of the Republican Party in the 1850s, which was dedicated to preventing the spread of slavery into new territories. Douglass campaigned for Republican candidates and used his influence to push the party towards more radical anti-slavery positions.

- Support for Abraham Lincoln: During the 1860 presidential election, Douglass endorsed Abraham Lincoln, recognizing him as the candidate most likely to oppose the expansion of slavery. Although initially critical of Lincoln’s cautious approach to emancipation, Douglass maintained a working relationship with the president. He met with Lincoln several times, urging him to take decisive action against slavery and advocating for the enlistment of African American soldiers in the Union Army.

- Emancipation Proclamation: Douglass played a significant role in shaping public support for the Emancipation Proclamation. Following the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam, Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, declaring that all slaves in Confederate-held territory would be freed as of January 1, 1863. Douglass hailed the proclamation as a crucial step towards full abolition and worked to recruit African American men to join the Union forces, recognizing that their participation was vital to the war effort and their own liberation.

- Post-Civil War Advocacy: After the Civil War, Douglass continued to fight for the rights of African Americans. He supported the passage of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery, and the 14th and 15th Amendments, which granted citizenship and voting rights to African Americans. Douglass held several government positions, including U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia and Minister Resident and Consul General to Haiti, using his influence to advocate for civil rights and social justice.

- Women’s Rights: Douglass was also a strong advocate for women’s rights. He attended the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 and supported the inclusion of women’s suffrage in the Declaration of Sentiments. His intersectional approach to social justice highlighted the interconnected struggles for racial and gender equality.

- John Mercer Langston:

Background

John Mercer Langston was born on December 14, 1829, in Louisa County, Virginia, to a biracial couple. His father, Ralph Quarles, was a wealthy white plantation owner, and his mother, Lucy Langston, was an emancipated African American woman of Native American and black descent. Despite his father’s relative wealth, Langston’s parents were not legally married due to anti-miscegenation laws, and he was born into a society deeply divided by racial lines.

Tragically, Langston’s parents died when he was only four years old, leaving him and his siblings orphaned. They were taken to Chillicothe, Ohio, to live with family friends. Chillicothe was a relatively progressive community with strong abolitionist sentiments, which profoundly influenced Langston’s early development. He attended a Quaker school and later Oberlin College, one of the first colleges in the United States to admit African American students. Langston earned a bachelor’s degree in 1849 and a master’s degree in theology in 1852. He subsequently became one of the first African Americans to receive a law degree from Oberlin College in 1854.

Contribution to Anti-Slavery

John Mercer Langston’s contributions to the anti-slavery movement and the fight for African American rights were significant and multifaceted. His work as an educator, lawyer, politician, and advocate for civil rights played a crucial role in advancing the cause of abolition and influencing the Republican Party’s policies.

- Legal and Educational Career: After receiving his law degree, Langston was admitted to the Ohio bar, making him one of the first African American lawyers in the United States. He began his legal career in Brownhelm, Ohio, where he also became the town clerk, making him the first African American elected to public office in the United States in 1855. Langston was also deeply involved in education. He served as the principal of the Normal and Preparatory Department at Wilberforce University, the nation’s first black college, in Ohio. His commitment to education for African Americans was a crucial aspect of his fight against slavery and for civil rights.

- Political Activism and the Republican Party: Langston became increasingly involved in the Republican Party, which was founded in the 1850s with a strong anti-slavery platform. He was a vocal advocate for the abolition of slavery and used his legal expertise to assist runaway slaves and fight for their freedom. He was an active participant in the anti-slavery movement, helping to organize and lead various abolitionist societies. Langston worked closely with other abolitionists to support the Underground Railroad, which helped escaped slaves find freedom in the North and Canada.

- Civil War Contributions: During the Civil War, Langston played a vital role in recruiting African American soldiers for the Union Army. He helped to raise the Massachusetts 54th Regiment, one of the first official African American units in the U.S. Army. His efforts in recruitment were instrumental in demonstrating the bravery and capability of black soldiers, which helped to shift public opinion and policy regarding African American participation in the military.

- Post-War Reconstruction: Following the Civil War, Langston continued his advocacy for African American rights during the Reconstruction era. He supported the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery, and the 14th and 15th Amendments, which granted citizenship and voting rights to African Americans. Langston’s political career flourished during Reconstruction. He served as a delegate to the Republican National Convention and was appointed inspector general of the Freedmen’s Bureau, an organization established to help newly freed slaves transition to citizenship. In this role, he worked to ensure that African Americans had access to education, employment, and legal protections.

- Howard University: In 1868, Langston became the dean of the law department at Howard University, a historically black university in Washington, D.C. He was instrumental in shaping the institution’s curriculum and ensuring that it provided a high-quality legal education to African American students. Under his leadership, Howard University Law School became a critical institution for training black lawyers and civil rights advocates.

- Political Career and Advocacy: Langston’s political career continued to advance as he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia in 1888, serving until 1891. He was one of the first African Americans elected to Congress from Virginia and used his position to advocate for civil rights and social justice. Langston also served as the U.S. Minister to Haiti and chargé d’affaires to the Dominican Republic from 1877 to 1885. In these diplomatic roles, he worked to promote positive relations between the United States and these nations, while also advocating for the interests of African Americans abroad.

- Harriet Tubman:

Background

Harriet Tubman was born Araminta Ross around 1822 in Dorchester County, Maryland, to enslaved parents Harriet Green and Ben Ross. Her exact birthdate is not known due to the lack of records kept for slaves. Tubman endured the harsh realities of slavery from an early age, suffering physical violence and witnessing the brutal treatment of other slaves.

In her early twenties, Tubman married a free black man named John Tubman and adopted his surname. Around 1849, fearing she would be sold further south, Tubman escaped from slavery, leaving her husband behind. She traveled by night, using the North Star and assistance from the Underground Railroad, a secret network of safe houses and abolitionists who helped runaway slaves reach freedom in the North or Canada.

After reaching Philadelphia, Tubman did not rest. Instead, she made it her mission to rescue her family and others still enslaved. She made 13 missions over a decade, rescuing approximately 70 slaves and guiding them to freedom, earning the nickname “Moses” for her leadership and bravery.

Contribution to Anti-Slavery

Harriet Tubman’s contributions to the anti-slavery movement were immense and multifaceted. Her direct actions in leading slaves to freedom, her work with the Union Army during the Civil War, and her involvement with the Republican Party significantly impacted the fight against slavery and the advancement of African American rights.

- The Underground Railroad: Tubman’s most famous contribution was her role as a conductor on the Underground Railroad. Starting in 1849, she returned to the South numerous times, risking her life to guide slaves to freedom. Tubman’s intimate knowledge of the terrain, coupled with her courage and resourcefulness, made her one of the most successful conductors in the history of the Underground Railroad. Despite a bounty on her head and constant threats of capture, Tubman continued her missions. She used various tactics to evade capture, including traveling during winter months when fewer people were on the roads and using songs and coded messages to communicate with escaping slaves.

- Civil War Contributions: During the Civil War, Tubman served as a scout, spy, and nurse for the Union Army. She joined the Union forces in South Carolina and used her knowledge of covert travel and intelligence gathering to assist the Union cause. One of her most notable military contributions was her leadership in the Combahee River Raid in June 1863. Tubman guided Union troops up the Combahee River in South Carolina, where they destroyed Confederate supplies and freed more than 700 slaves. This raid demonstrated her exceptional skills and commitment to the Union and the abolitionist cause.

- Republican Party Involvement: Tubman’s involvement with the Republican Party was aligned with her abolitionist activities. The Republican Party, founded in the 1850s, had a strong anti-slavery platform, and Tubman supported its candidates and policies. She worked alongside prominent Republicans and abolitionists, such as Frederick Douglass and William Seward, to further the cause of abolition. Although she was not a politician, Tubman’s actions and her role as a symbol of the abolitionist movement provided significant moral and practical support to the Republican Party’s anti-slavery agenda.

- Post-War Activities and Advocacy: After the Civil War, Tubman continued to advocate for the rights of African Americans and women. She settled in Auburn, New York, where she purchased property from Senator William Seward, a prominent Republican and abolitionist. Tubman was involved in various humanitarian efforts, including establishing the Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged, which provided care for elderly African Americans. She also supported the women’s suffrage movement, working alongside suffragists like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

- Recognition and Legacy: Despite her monumental contributions, Tubman faced financial difficulties and struggled to receive the recognition and compensation she deserved. She fought for years to obtain a military pension for her service during the Civil War, eventually receiving a widow’s pension after her second husband’s death and later a small additional pension for her own service. Tubman’s legacy as a freedom fighter, humanitarian, and advocate for justice has endured. She is celebrated as an iconic figure in American history, symbolizing courage, resilience, and the relentless pursuit of freedom and equality.

- Conclusions

Since the conclusion of the American Civil War, African Americans have historically remained among the most steadfast Republican voters. This loyalty, however, has not stemmed from an exceptional commitment by the “Grand Old Party” to address the concerns of the black population, but rather from a lack of viable political alternatives.

The typical black Republican supporter tends to be a middle-aged individual who prioritizes their personal interests over collective considerations. Preferring not to align with an electoral monolith, the black Republican exhibits a lower level of racial consciousness compared to the majority of their community members. Consequently, their focus often gravitates towards issues that resonate more with white Republicans, such as tax policy or national security, rather than traditionally significant concerns for black America, such as social programs or interracial relations.

Acknowledging the constraints and deficiencies in its standing within the black population, the Republican Party persists in implementing various measures aimed at enhancing its influence in the African American community. These efforts include advocating for educational reform, endorsing the liberalization of the criminal justice system, and emphasizing how specific socio-economic policies contribute to the welfare of black Americans.

However, the Republicans’ success in securing the votes of the black population from the Democrats hinges largely on the “Grand Old Party’s” capacity to devise compromise solutions to pressing issues facing the African American community, particularly in the aspects of interracial relations.

SOURCES

- “2016 Republican Party Platform” http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/2016-republican-party-platform . University of California, Santa Barbara. July 18, 2016. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- Abraham Lincoln | Biography, Childhood, Quotes, Death, & Facts http://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Abraham-Lincoln&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwieqsKljbqGAxV7_7sIHWASC14QFnoECAQQAg&usg=AOvVaw2PrPBltu9v463fEA-eP1Sq

- Abraham Lincoln | The White House http://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/abraham-lincoln/&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwieqsKljbqGAxV7_7sIHWASC14QFnoECAAQAw&usg=AOvVaw0MzdSUtYMn8OG_hz-JLQuy

- Brownstein, Ronald (November 22, 2017). “Where the Republican Party Began” http://prospect.org/power/republican-party-began/ . The American Prospect. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- Democratic-Republican Party | Definition, Beliefs & History http://study.com/learn/lesson/democratic-republican-party-beliefs-history-thomas-jefferson.html

- Frederick Douglass | Biography, Accomplishments, & Facts http://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Frederick-Douglass&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwjW4qCLjrqGAxUUhP0HHVftCxwQFnoECAUQAg&usg=AOvVaw3qAU3wk0-q0wMKr0_sNAIx

- Frederick Douglass – Narrative, Quotes & Facts http://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/frederick-douglass&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwjW4qCLjrqGAxUUhP0HHVftCxwQFnoECAkQAg&usg=AOvVaw3gF2otISYq_Qb725ApQRbA

- From the Origins to the Present-Day Relationships between the African American Community and the Republican Party http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10052273/

- Harriet Tubman – National Women’s History Museum http://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/harriet-tubman&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwjClqXajbqGAxVbhv0HHdMwC_YQFnoECAoQAg&usg=AOvVaw1P3xkMdB6XjlMmfommfMaz

- John Mercer Langston (1829-1897) http://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/langston-john-mercer-1829-1897/&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwjj1IDvjbqGAxWrhP0HHWEbBUIQFnoECAsQAg&usg=AOvVaw1kp5r_L7i7wHlJtINibs89

- John Mercer Langston | Abolitionist, Educator, Lawyer http://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Mercer-Langston&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwjj1IDvjbqGAxWrhP0HHWEbBUIQFnoECAEQAw&usg=AOvVaw0ViAuaVZEeu481O6EUUPbr

- Lincoln, Abraham (1989). Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865 http://books.google.nl/books?id=UWJStTs8-A4C&pg=PA120&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false . Library of America. p. 120. ISBN 978-0940450639.

- Salmon P. Chase http://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.history.com/topics/us-government-and-politics/salmon-p-chase&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwjtr4zSjLqGAxXJ8LsIHW_8Cc8QFnoECAQQAg&usg=AOvVaw0G4_tZjL4ChZevMjO2rbXB

- Salmon P. Chase | chief justice of United States http://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Salmon-P-Chase&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwjtr4zSjLqGAxXJ8LsIHW_8Cc8QFnoECAkQAg&usg=AOvVaw3ZHOO36H7o-CPvyTjEwSvQ

- Thaddeus Stevens | Abolitionist, Civil War Politician http://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Thaddeus-Stevens&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwiN6u7pjLqGAxXmhP0HHfGYAp0QFnoECAAQAw&usg=AOvVaw2MeyXqOlKsQ-_CsiYc_b6f

- Thaddeus Stevens – Quotes, Lincoln & Reconstruction – Biography (Bio.) http://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.biography.com/political-figures/thaddeus-stevens&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwiN6u7pjLqGAxXmhP0HHfGYAp0QFnoECAMQAg&usg=AOvVaw2YH3WyepikKLcv_iXGGMu1

- William Seward – Early Life, Facs & Career http://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/william-seward&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwinsKuejLqGAxWRnf0HHRGUAeUQFnoECAUQAw&usg=AOvVaw2IdnozKdFtib2VYcioGVE3