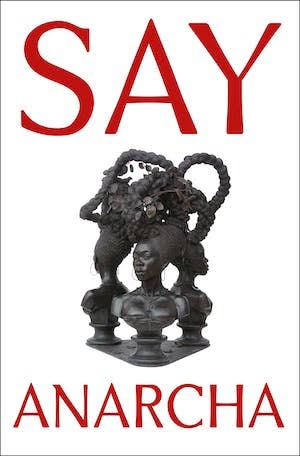

Anarcha, at the youthful age of 17, found herself enslaved and subjected to a series of ground-breaking but excruciatingly painful surgeries between 1846 -1849. What sets her apart is not merely the physical endurance she displayed during these procedures, but her enduring legacy that challenges the narrative of forgotten women in medical history. In acknowledging Anarcha’s contribution, we acknowledge the countless other women who, too, played a crucial role in shaping the landscape of gynaecology.

For years, J.Marion Sims was regarded as the father of modern gynaecology, however he now faces a critical re-evaluation as history shifts is focus and stands tall to the unsung heroes of the field—women who courageously endured experimental surgeries to pave the way for contemporary gynaecological advancements. Although Sims held a prominent place in the annals of medicine, it is the resilient women subjected to his experiments who truly deserve recognition. Among them stands Anarcha Westcott, a name resonating through the corridors of time, defying the usual fate of being forgotten like so many others.

For generations, the stories of Anarcha Westcott and other women subjected to early gynaecological practices remained unknown, often overshadowed by the accounts of J. Marion Sims. Anarcha, pregnant at the Westcott Plantation near Monogamy suffered a stillbirth that left her with a damaged pelvis after an excruciating three-day labour. Dr. Sims, lacking prior experience in forceps delivery, was brought in, initiating a series of interventions. Days later, Anarcha’s after birth examination revealed a tragic vaginal rip, leading to Vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistula complications. Anarcha endured a staggering 30 surgeries before Dr.Sims was able to eventually close up he vaginal opening, vaginal opening, concluding a painful chapter. Anarcha’s narrative, once eclipsed, now emerges as a testament to the resilience of women who endured unspeakable hardships, challenging the historical narrative and prompting a revaluation of the early foundations of gynaecology.

Following inquiries and investigations into J. Marion Sims’ early life and the kind of surgery he performed on black women, he was the subject of numerous disputes. Sims’s craving for recognition was overwhelming, and he was certain that this procedure would get him the notoriety he sought. He performed his first surgery on her without anaesthetic because he was convinced that black women did not experience pain. In his book, he claimed that during the surgery, all she did was scream, and on occasion, he would call in other medical professionals to help hold her down. Although Anarcha underwent more procedures, it is clear that she was not the only one. Two other women, named Lucy and Betsey, were also mentioned. The status of the other women is still unknown. After almost two years, he claimed to have cured her injuries with silver thread and a clamp suture, a procedure that would subsequently be abandoned.

One of the unpleasant dimensions of Marion Sims’ historical narrative lies in his intentional disregard for available medications that could have reduced the suffering of the women subjected to his barbaric experimental surgeries. Despite having access to remedies, Sims opted for untested surgical procedures, treating these women more as lab rats than individuals in need of help. The surgeries took hours, they were bared in front of men carefully watching them being in agony When we think about this, we think about more than just the anguish; we think about how these women’s dignity was also stripped away and the violation of their humanity for medical experiment.

While acknowledging that Sims also treated white women, a stark disparity emerges— white patients were afforded the privilege of anaesthesia during their procedures. Sims’ departure from Alabama in the 1850s and subsequent establishment of a women’s hospital in New York City in 1855 marked a shift in his career trajectory. Acclaimed as a skilled surgeon, particularly for his treatment of white women, the unsettling truth persists: the techniques perfected on the bodies of black women laid the groundwork for Sims’ later successes. This highlights the deeply troubling ethical considerations embedded in the history of gynaecology, where the exploitation of vulnerable populations played an unsettling role in medical advancements.

In examining the accounts of the women who were experimented, it is important several things, neither Sims nor is assistant Bozeman were acting out of altruistic motive. The women undergoing these experiments were unable to provide informed consent, amplifying the ethical dilemmas surrounding these procedures. The so-called “cure” they endured merely meant a return to plantations, to be forced to breed more enslaved persons and to be raped by overseers, and by their enslaver. Furthermore, it is imperative to dispel the notion that either Sims’s clamp suture or Bozeman’s button suture represented a genuine cure for obstetric fistula, although it is tempting to see them as heroic.

Re-examining the historical account reveals that Anarcha and the other women were the real trailblazers, intrepidly enduring unspeakable suffering in order to further our understanding of medicine. Even though their tales were frequently ignored, they now need to be heard as we change our perception of the origins of contemporary gynaecology. We are able to comprehend the intricacies and moral dilemmas that have guided the development of medical procedures because of their fortitude and selflessness. Understanding the intricacies of medical history requires acknowledge ing and respecting their experiences.

Sources