Delving into the corridors of history, one stumbles upon a captivating yet peculiar chapter — the tale of menstruating men. Unravelling the intricacies of this historical phenomenon reveals a mosaic of myth, ritual, and symbolism that traverses the boundaries of time and culture. This exploration takes us on a more extended odyssey, offering a nuanced understanding of the multifaceted story of men experiencing a monthly flow akin to menstruation.

During Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt in 1798. The notion of men menstruating, as noted by French physicians at the time, was likely a result of their encounters with a prevalent medical condition in the region, namely haematuria associated with schistosomiasis.

Schistosomiasis, a parasitic disease caused by Schistosoma worms, particularly S. haematobium, can lead to symptoms such as bloody urine, a condition known as haematuria. The disease is transmitted through contact with contaminated freshwater harbouring the larvae of the parasitic worms. Egypt, with its extensive network of irrigation canals and the Nile River, provided an environment conducive to the spread of schistosomiasis.

In the early 19th century, when European physicians observed the high incidence of haematuria among Egyptian men, they may not have initially connected it to schistosomiasis. The prevalence of bloody urine could have been misinterpreted, leading to the curious assertion that Egypt was the only country where men menstruated. This misconception likely arose from a lack of understanding of the underlying parasitic infection.

The link between haematuria and schistosomiasis became clearer in the mid-19th century when the German parasitologist Theodor Bilharz identified and described the parasite responsible for urinary schistosomiasis. The disease subsequently became known as bilharzia in his honour.

Bilharz’s groundbreaking work not only provided a clear understanding of the cause of haematuria in Egyptian men but also contributed significantly to the broader understanding of parasitic diseases and their transmission. The term “menstruation” used in this context was likely a historical misinterpretation rooted in the visible symptom of bloody urine rather than a true understanding of the underlying parasitic infection.

Ancient mythology serves as a fascinating backdrop to the concept of menstruating men, offering a glimpse into the ways in which cultures perceived the divine and the interplay of gendered symbolism.

In Mesopotamian mythology, the goddess Ishtar stands as a prominent example of this divine synthesis. Ishtar, representing both love and war, encapsulates the duality inherent in the cosmic order. Within her divine essence, the symbolism of menstruation becomes a metaphor for the cyclical nature of existence — a rhythmic dance between life, death, and rebirth. Ishtar’s menstrual cycles are intricately woven into the broader narrative of cosmic balance, emphasising the interconnectedness of masculine and feminine forces.

Similarly, ancient Egyptian mythology intertwines menstrual symbolism with lunar cycles and the goddess Isis. As the lunar phases mirrored the waxing and waning of menstrual cycles, Isis became a conduit for the sacred feminine. Here, the ebb and flow of menstrual symbolism served not only as a reflection of natural rhythms but also as a spiritual metaphor, connecting the divine with the earthly.

Religious rituals played a pivotal role in shaping and reinforcing these beliefs. In certain ancient societies, men participated in rituals that involved the simulation of menstruation to establish a connection with the sacred feminine. The act of simulated menstruation was not merely a symbolic gesture but a ritualistic approach designed to honour the delicate equilibrium between masculine and feminine energies within the cosmic order. These rituals underscored the belief in a harmonious cosmic balance that required the active participation of both genders.

The convergence of mythology and religious practices in these ancient cultures demonstrates the profound impact of menstruating men as a symbolic construct. It transcends mere biological functions and delves into the realm of spirituality, where the cyclical nature of menstruation becomes a powerful metaphor for the eternal cycles of creation, destruction, and regeneration that govern the cosmos. The ancient mythologies and rituals surrounding menstruating men stand as a testament to humanity’s perennial quest for understanding the profound mysteries of existence and the divine.

As civilisations evolved, so did the interpretations of menstruating men. Beyond mere myth, some tribal cultures incorporated the belief into practical cultural practices. Among the Sambia people of Papua New Guinea, young boys participated in rituals that linked the ingestion of semen to the acquisition of male strength and wisdom, paralleling a form of ritualised menstruation.

In South Asia, the hijra community, recognised historically as a third gender, engaged in practices that symbolically linked to menstruation following castration. This community, with a rich history in the Indian subcontinent, reflects a unique blend of ancient traditions and a distinct interpretation of gender and identity.

The medieval period in Europe witnessed the prevalence of alchemy and mysticism, with symbolic language concealing deeper truths. Menstruating men found expression in alchemical texts, where the merging of opposites was a central theme. Metaphorical language hinted at the idea of men undergoing menstruation as a pathway to spiritual enlightenment, embodying a purification or transformative experience.

Hermetic traditions, influenced by the ancient Egyptian god Thoth, emphasised divine androgyny, where masculine and feminine principles coexisted within each individual. The alchemical process, seen as a means to harmonise opposing forces, featured menstruation as a symbol of purification and transcendence.

Beyond religious and alchemical contexts, the theme of menstruating men permeated literature and art. Renowned Irish poet William Butler Yeats, a key figure in the Irish literary revival, explored mystical and esoteric themes in his work, delving into the transcendent, androgynous state where both men and women could access higher realms of consciousness.

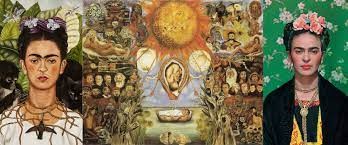

Artists like Frida Kahlo, a prominent figure in surrealism, harnessed menstrual imagery in their art to challenge established societal norms. Kahlo’s self-portraits, characterised by visceral depictions of the female body, shattered traditional representations of femininity. Instead, they confronted the viewer with the raw, complex realities of gender identity, making a powerful statement about the fluidity and intricacy of human experiences.

The historical narrative of menstruating men unfolds as a rich tapestry interwoven with threads of mythology, ritual, symbolism, and cultural practices. Across diverse civilisations and epochs, this enigmatic concept persists, offering a profound lens through which to examine the evolving understanding of gender, identity, and the interconnectedness of seemingly disparate elements in the human experience. The story of menstruating men serves not only as a historical curiosity but as a reflection of the perennial fascination humanity holds for the intricate dance between the sacred and the mundane in the human journey.

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schistosoma_haematobium

- https://getruth.ca/blogs/ruth-blog/periods-through-history-a-menstrual-timeline#:~:text=The%20Ancient%20Civilizations,-The%20use%20of&text=Historians%20believed%20that%20tampons%20were,backgrounds%20were%20able%20to%20benefit.

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/519030

- https://melmagazine.com/en-us/story/blood-brothers-the-painful-history-of-male-menstruation