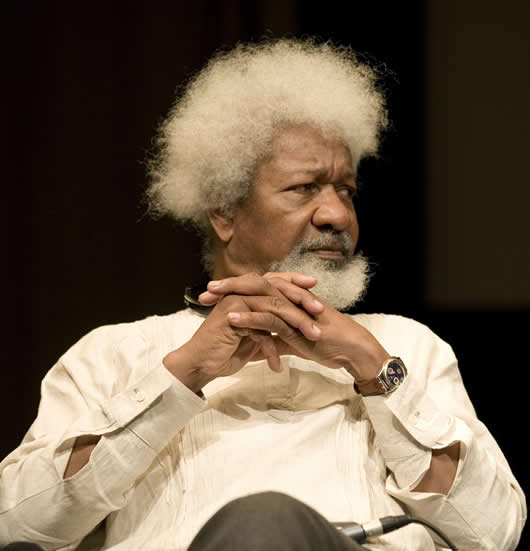

Wole Soyinka, born on July 13, 1934, in Abeokuta, Nigeria, is a prolific playwright, poet, novelist, and political activist who has profoundly influenced African literature and thought. Known for his satirical and poignant style, Soyinka’s work often explores the complexities of power, cultural identity, and political integrity. As the first African laureate of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1986, Soyinka’s accomplishments have earned him global recognition. His writings address both the spirit and the struggles of his homeland, Nigeria, and examine broader themes of justice and freedom, rooted deeply in African traditions.

Growing up in a Christian household with Yoruba influences, Soyinka’s upbringing merged traditional beliefs with a modern worldview. His mother, Grace Eniola Soyinka, was known as a local activist and shopkeeper, while his father, Samuel Ayodele Soyinka, was a respected Anglican minister and school headmaster. Known as a curious child, Soyinka’s incessant questioning earned him the reputation of one who might “kill you with his questions.” His formal education began at Government College in Ibadan, Nigeria, where he excelled academically. Soyinka continued his studies at University College in Ibadan before moving to England, where he earned a degree in English from the University of Leeds in 1958. His time at Leeds, where he also served as editor of The Eagle, the university magazine, allowed him to refine his voice and explore Western literature and drama, later earning an honorary doctorate from the university in 1973.

In England, Soyinka began to establish his literary career, working as a dramaturgist at London’s Royal Court Theatre from 1958 to 1959. His early plays, such as The Swamp Dwellers and The Lion and the Jewel, combined Western influences with African themes. The Lion and the Jewel (1959), a comedic play set in a Nigerian village, satirizes the cultural clash between tradition and modernity through the story of a proud, Western-educated schoolteacher and a traditional village chief competing for the love of a young woman. This blend of humor and social critique set the tone for much of Soyinka’s later work.

In 1960, upon returning to Nigeria with a Rockefeller bursary to study African drama, Soyinka became an influential figure in Nigeria’s cultural and political landscape. He founded the 1960 Masks and Orisun Theatre Company, where he produced his own plays and performed as an actor, often using his stage as a platform for social criticism. One of his first significant works, A Dance of the Forests (1960), was commissioned for Nigeria’s independence celebrations. The play, however, shocked audiences by challenging idealized notions of the nation’s past and present, highlighting Soyinka’s view that romanticizing history ignores the pressing realities of the present. This inclination to reveal uncomfortable truths marked him as both a celebrated and controversial figure in Nigerian society.

As a dramatist, Soyinka’s unique style reflects the influence of both Western literature and traditional African theater. His plays incorporate Yoruba mythology, dance, music, and rituals. Ogun, the Yoruba god of iron and war, is a central figure in Soyinka’s writings, symbolizing resilience and the complexities of power. Soyinka’s serious plays, such as The Strong Breed (1963), The Road (1965), and Death and the King’s Horseman (1975), delve into existential and moral themes, while his satirical works like Kongi’s Harvest (1965) critique political leadership and societal hypocrisy.

Soyinka’s political involvement became particularly pronounced during the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970). Advocating for peace, he published articles calling for a ceasefire, which led to his arrest on charges of conspiring with the Biafran rebels. He spent 22 months as a political prisoner, during which he wrote Poems from Prison, later republished as A Shuttle in the Crypt (1972). His prison memoir, The Man Died (1972), documents his harrowing experience, describing both the physical hardships and the mental resilience required to survive his imprisonment. Despite his ordeal, Soyinka remained a steadfast critic of authoritarianism, famously stating, “The man dies in all who keep silent in the face of tyranny.”

Beyond drama, Soyinka’s literary output includes novels, essays, and poetry, all of which reflect his intellectual depth and commitment to justice. His novels The Interpreters (1965) and Season of Anomy (1973) offer critiques of Nigerian society through complex narratives and symbolic storytelling. The Interpreters, for instance, follows the lives of six Nigerian intellectuals as they grapple with the disillusionment and corruption in their country, presenting a rich and introspective view of postcolonial Nigeria. Season of Anomy draws from Soyinka’s imprisonment, reimagining the Orpheus and Eurydice myth within Yoruba mythology to explore themes of political oppression and resilience.

In addition to his literary achievements, Soyinka has been an influential voice in Nigerian academia, holding teaching positions at the University of Ibadan, the University of Lagos, and Obafemi Awolowo University (formerly University of Ife), where he was a professor of comparative literature. He has also been invited as a visiting professor at international universities like Cambridge, Sheffield, and Yale. His engagement with academia reflects his lifelong commitment to education, social justice, and the promotion of African literature on the world stage.

Soyinka’s essays, collected in works like Myth, Literature, and the African World (1976) and Art, Dialogue, and Outrage (1988), provide a scholarly analysis of African art and culture, challenging Western perceptions and promoting an understanding of African values and philosophies. His Reith Lectures, published as Climate of Fear (2004), explore the impact of fear on global society, drawing from both African and Western perspectives.

Even in his later years, Soyinka continued to voice his concerns about Nigeria’s political landscape and the role of intellectuals in shaping society. His outspoken criticism of corrupt leadership and military dictatorship made him a target of the Nigerian government, leading to periods of exile. In 2010, Soyinka founded the Democratic Front for a People’s Federation, seeking to advance democratic principles in Nigeria. His activism and public statements have often highlighted the need for forgiveness and resilience, values he encourages Nigerians to adopt in their pursuit of a just society. For instance, after Nigeria’s 2015 elections, he urged citizens to embrace a Mandela-like spirit of forgiveness towards Muhammadu Buhari, despite Buhari’s past as a military ruler.

Soyinka’s recent publications, including his memoir You Must Set Forth at Dawn (2006) and his novel Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth (2021), demonstrate his enduring commitment to storytelling and social critique. In Chronicles, he tackles Nigeria’s contemporary challenges through satire, addressing issues of corruption, identity, and the moral decay affecting society. Through his continued literary contributions, Soyinka maintains his position as Nigeria’s foremost man of letters, unafraid to challenge political and social injustices.

Soyinka’s legacy is one of resilience, creativity, and profound influence. His blend of Yoruba mythology, African traditional theater, and Western literary forms has created a unique voice that speaks to both African and global audiences. His fearless advocacy for democracy and human rights, coupled with his groundbreaking work in literature, has made him a timeless figure whose impact transcends borders. With a career that spans over six decades, Wole Soyinka remains a formidable force in African literature, embodying the intellectual and cultural richness of his heritage.

Sources

- https://www.biography.com/writer/wole-soyinka

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1986/soyinka/biographical/

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Wole-Soyinka